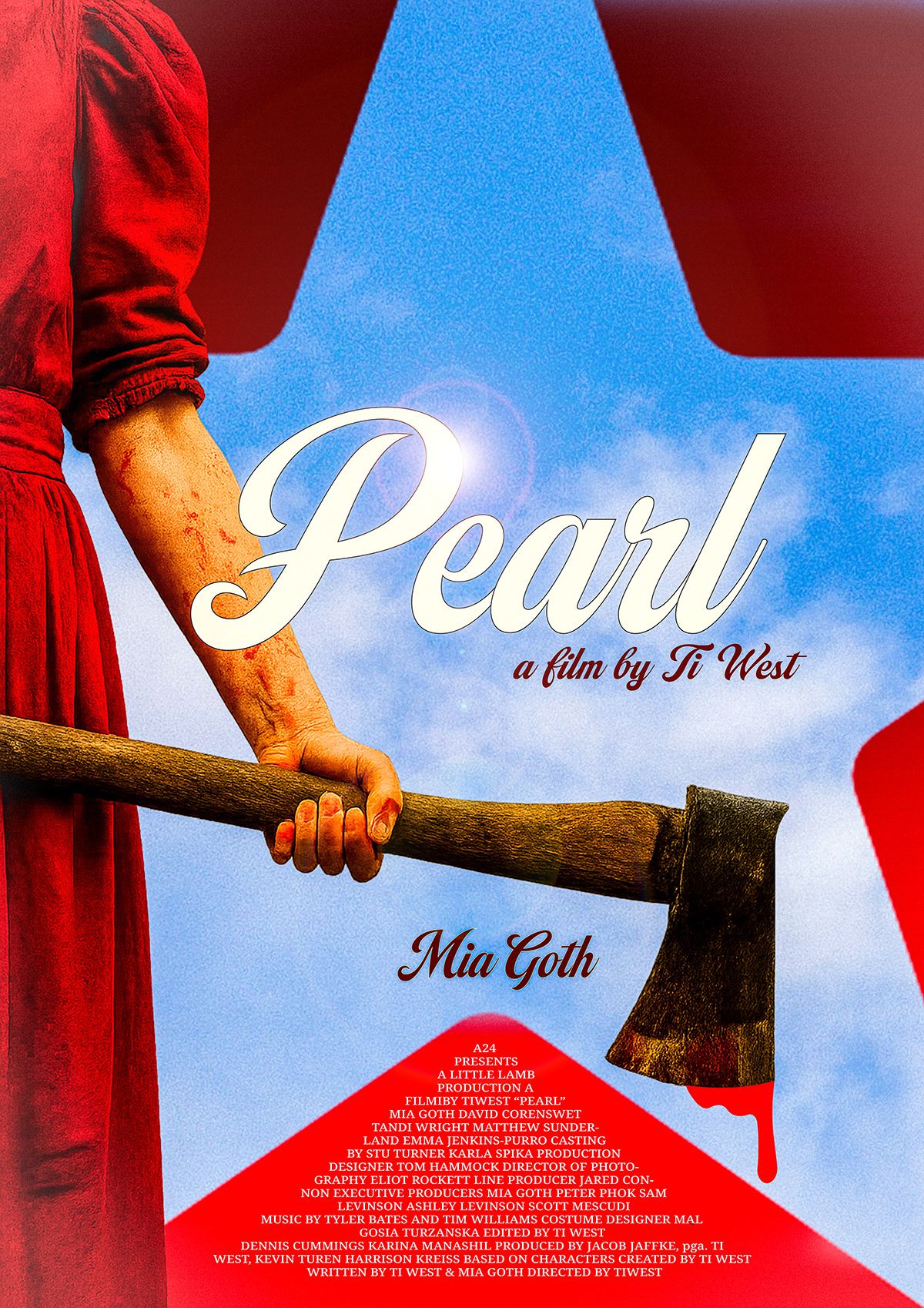

Part One - Pearl

A prequel to X, and chronologically first of the films, Pearl sets this tone for the rest of the movies. Pearl is a small-town Texas farmer girl in the plightful year 1918. She faces the hardships of the Spanish Flu pandemic, which has paralyzed her father and put great strain between her and her mother. Pearl’s husband, Howard, has gone to fight in the Great War, leaving the two of them to pick up the slack on the farm. These challenges drive her to insanity and murder, as all she wants is to escape the farm and chase her dreams of being a dancer on the silver screen. She starts off with animal cruelty, killing geese and feeding them to alligators, but quickly shifts her target to people as she gets into a brutal fight with her mother, whom she knocks into a stove and burns to near death. From here her victims grow to her sister-in-law, the local projectionist she's having an affair with, and her impaired father. The viewer's mind is stained with visions of the rotting, beaten, and burned bodies of her victims. These acts of barbarous murder committed by Pearl and their imagery directly play into Burke’s idea of the sublime, as it presents the viewer with a life-or-death image and the horrifying murderous nature of an individual. Watching her indiscriminately tear into her victims evokes this sublime horror, making the viewers fear for their lives.

Pearl also showcases the sublime through pornographic elements. Pearl is at the local theater any chance she can get; it is her happy place. Naturally her frequent beauty in the place is noticed by the projectionist, who she becomes close with. Their relationship becomes a showcase for sublime sexual explicitness in the film. At first she develops a crush on the man, and while not being able to engage sexually with him she attempts to replicate these actions in a three minute sex scene with a scarecrow alongside the road. The scarecrow is the closest she believes she can get to him without betraying her husband. She carries on spending time with the projectionist, played by David Corenswet, and he shows her films the world had never seen. Pornographic stag films too dirty for the public. She quickly throws her morals out the window and engages in full infidelity with the man. While the imagery of these relations may not be as pornographic as the next two films in the trilogy, they are sublime in a different sense. Pearl herself is shocked by her own actions of infidelity. Her betrayal of her own morality is its own sense of sublime to her and the viewer, as her wrongdoing can end her life as she knows it. While she may have received pleasure from this escapade, Burke states,”the idea of pain, in its highest degree, is much stronger than the highest degree of pleasure.” The pain that ensues from her Christian guilt in the film is so great it becomes sublime.